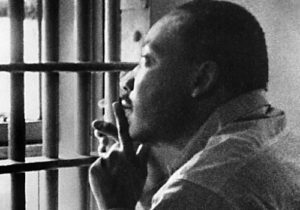

April 20, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. with Ralph Abernathy leaving the Birmingham Jail after being arrested for 8 days.

In the 1960s Birmingham, Alabama was the largest industrial city in the South and according to Martin Luther King Jr. the most segregated city in America.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) joined the local Birmingham movement, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), to direct a campaign against segregation by putting pressure on Birmingham downtown merchants. Its leaders, Martin Luther King Jr. and Fred Shuttlesworth were determined to raise national awareness by testing Supreme Court desegregation laws. After careful planning, strategizing and fundraising they conceived a plan called Project C.

They started by approaching the newly elected mayor, Albert Boutwell, with a list of grievances and calling for an immediate end to segregation in lunch counters, stores, restrooms and racist hiring practices.

Demonstrations

Peaceful protesters were attacked by police and dogs while being televised nationally and internationally.

Demonstrations started on April 3 with protesters staging sit-ins at various lunch counters, followed by marches to city hall and voter registration efforts. As expected all demonstrators ended up in Birmingham jails. On April 6 Dr. King led a prayer march in downtown Birmingham that mobilized a large number of people, police moved in with dogs and sticks colliding with protesters in front of a large media presence. Dr. King’s marches were peaceful and activists were trained to not react violently when police hit or picked at them. The attack on peaceful protesters was televised nationwide on evening news programs and on newspapers.

A court injunction was issued against all future demonstrations and prohibited 133 civil rights leaders from encouraging or participating in protests.

King and the rest of the Southern Christian Leadership Congress (SCLC) leaders decided to break the law as they thought that the order was designed to perpetuate tyranny under the guise of maintaining law and order. King, Alberny and Hibbler along with 50 other activists were arrested and sent to jail.

Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Martin Luther King Jr. wrote Letter from a Birmingham Jail on the margin of a newspaper.

During his time in jail King wrote Letter from a Birmingham Jail in response to an advertisement by a group of white clergymen that appeared in the Birmingham News. The clergymen attacked the protests as unwise and untimely and not justified. King defended his non violent resistance as a catalyst for negotiations with the authorities but because authorities failed to negotiate they had no option but to protest. He wrote the letter on the margin of a newspaper, it was first published by The Liberator in May 1963. Letter from a Birmingham Jail became an important text in the African American Civil Rights Movement.

Children’s march

On May 2, 1963 the Children’s Crusade was launched in Birmingham.

As the number of black adults willing to go to jail and sacrifice their jobs diminished the SCLC decided to use students instead as demonstrators. On May 2nd over 1,000 students ranging from 6 to 18 years old marched on the streets of Birmingham to a large crowd of cheering adults. Police loaded them in school buses and took them to jail.

The following day about 1,000 students assembled at the Sixteen Street Baptist Church were barricaded by police using high pressure fire hoses and loose dogs to keep them inside. These images were broadcast across the nation and internationally bringing publicity to King’s cause. Many criticized his tactic but he argued that “by demonstrating children are gaining a sense of their own stake in freedom and justice”.

Demonstrations gradually grew in size as well as police reaction. As many as 2000 people had been jailed before negotiations started.

Negotiations

The Justice Department sent an envoy to encourage negotiations between the city of Birmingham and Martin Luther King. The settlement, known as the Birmingham truce agreement consisted in:

- Desegregation of lunch counters, fitting rooms, restrooms and drinking fountains in all downtown stores within 90 days.

- Hiring of blacks in clerical and sales positions within 60 days.

- Release of prisoners.

- Establishment of permanent communication between black and white leaders.

Reactions

Some black critics believed King had given up their protest weapon in exchange for mere promises. The governor disavowed the settlement and called for a boycott of stores that desegregate. The Ku Klux Klan threatened with violence and bombed the house of King’s brother, Alfred Daniel King, and the Gaston Motel where civil right leaders were staying. Police were randomly beating blacks and stores were set on fire. To avoid further violence President Kennedy sent 3,000 federal troops to restore peace. Eventually Mayor Albert Boutwell honoured the settlement.

The events at Birmingham were a turning point in African American civil rights, the beginning of the end of the struggle for freedom.